Simple plastics made from polyolefins such as films or carrier bags have become an integral part of our everyday lives, but are rarely recycled. Junior Professor Robert Geitner wants to give these food packaging materials a new lease of life. At his Physical Chemistry/Catalysis Group, he is researching new potential applications for the materials. His vision is to turn thin plastic films into Kevlar vests.

Whether it's cling film, carrier bags or milk cartons - as much as packaging like this makes our everyday lives easier, it also harms our environment. Polyolefin-based materials, which include polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP), are currently hardly ever recycled. Making them more durable and environmentally friendly is a goal that chemist Prof. Robert Geitner works towards every day. The head of the Physical Chemistry/Catalysis Group at TU Ilmenau researches simple plastic compounds known as polyolefins. They are produced from oil or natural gas, are frequently used in food packaging or the construction industry due to their elastic and resilient properties and are ultimately stored in landfills or incinerated. The young professor would therefore like to develop a process that makes it possible to reuse plastic on a large scale. His vision: transforming plastic films into Kevlar vests.

Clothing, reusable containers or rubber tires - for Prof. Geitner, there are many conceivable ways to recycle plastic packaging made from polyolefins. However, the junior professor explains that what currently makes recycling these materials difficult is the lack of economic incentives on the one hand and their high chemical resistance on the other:

The materials have a very long shelf life and there are currently no microorganisms that can decompose them. This means that they remain in our environment for years, polluting our nature and oceans. The materials are often mechanically broken down until they enter our food cycle as microplastics - with consequences for our health and the environment.

The chemical properties of polyolefins make it difficult to recycle plastics, as polyolefins are considered inert and do not react with many substances. Their chemical bonds are very stable and it takes a lot of energy to break them up and change them - a hurdle that Prof. Geitner wants to overcome with the help of catalysis, a chemical process in which the speed and energy requirements of a chemical reaction are influenced:

Our approach is to break up the structure of polyolefins in a targeted and energy-saving manner and enrich them with other functional molecular groups. Our aim is to create new, even more stable molecules.

This would not only allow plastic packaging to be recycled, but also save valuable, scarce raw materials, says the chemist.

In a series of experiments, Prof. Geitner wants to test the reaction of polyolefins with various molecules that act as catalysts under controlled conditions. Depending on whether and how quickly new molecular compounds are formed, the scientist can determine the optimum molecular structure of the optimal catalyst. To do this, he uses artificial intelligence to predict new potential molecules. The computer-aided evaluation allows a large number of different substances to be examined virtually for their suitability as catalysts based on targeted experiments.

Prof. Geitner's research aims to minimize the impact of packaging waste on the environment, conserve fossil resources and contribute to the establishment of a circular economy:

I want to develop a process in which plastics can be converted for a wide range of applications in the circular economy. I hope this will be possible in 20 to 30 years' time, when the circular economy has become established in Germany and worldwide.

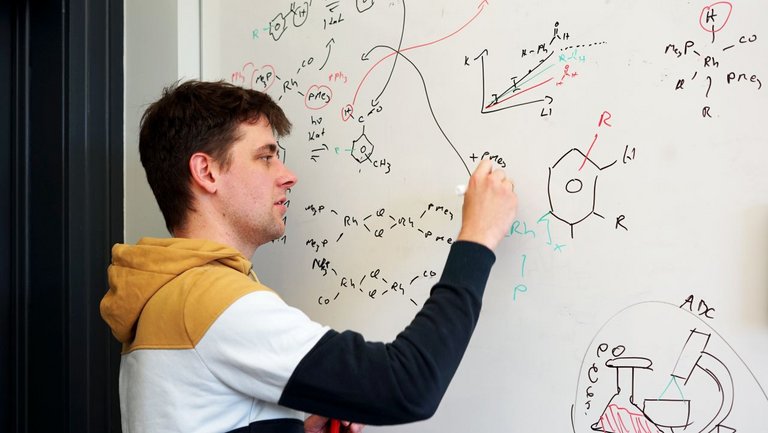

Prof. Robert Geitner in the chemistry lab

Contact

Jun.-Prof. Robert Geitner

Head of the Physical Chemistry/Catalysis Group